In 2023, the Biden administration collaborated with environmental groups to implement measures aimed at protecting the endangered Rice’s whale species. A key aspect of this agreement included speed restrictions for oil and gas vessels operating in specific areas of the Gulf of Mexico. However, recent developments suggest that these protections might be rolled back, raising concerns about the impact on Rice’s whales and the broader marine ecosystem.

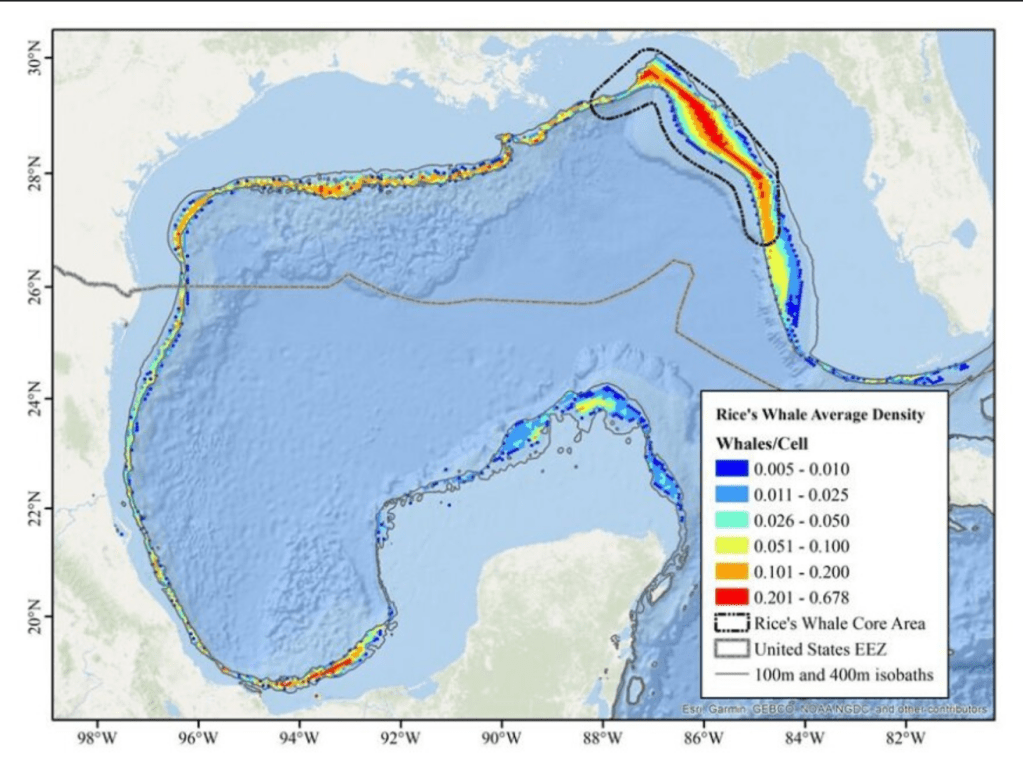

Rice’s whales (Balaenoptera ricei) are the most endangered whale species, with an estimated population of around 100 individuals. These whales primarily inhabit the northern Gulf of Mexico, with most sightings occurring in waters 100–400 meters deep, particularly off the coast of Alabama and the western coast of Florida. As they have a small population size, there is low genetic diversity and reproduction rate. They do not reach sexual maturity until year 9, carry for 10-12 months, and calves feed on their mothers for 1 year.

The major threats toward them are vessel strikes, noise pollution from vessels, oil spills and other pollutants. Increased ship noise can disrupt their communication, navigation, and feeding behaviors. Several commercial shipping lanes coincide with Rice’s whale habitat.

The potential removal of these speed limits could increase threats to this already vulnerable species.

This decision reflects a broader debate over balancing environmental conservation with economic interests, particularly in the oil and gas industry. While industry stakeholders argue that speed restrictions slow down operations and increase costs, conservationists emphasize the importance of protecting one of the world’s rarest whale species from further decline.

Conservation Success Stories

The small number of Rice’s whales does not mean they are a lost cause as there are many cases that can be highlighted where legal protections, conservation efforts, and habitat restoration have successfully increased animal populations. Here are a few examples:

Humpback Whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) nearly driven to extinction due to commercial whaling in the 19th and 20th centuries. By the 1960s, their populations had plummeted, with some estimates suggesting a decline of up to 90%.

The International Whaling Commission (IWC) imposed a moratorium on commercial whaling in 1986 (International Whaling Ban). which gave humpbacks and other whale species a chance to recover. Countries like the U.S., Australia, and Brazil enforced strict protections, banning whale hunting entirely.

Hawaiian Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary (established in 1992) protects breeding grounds. Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary (U.S.) and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park (Australia) also play a crucial role in conservation. In South America, the creation of the South Atlantic Whale Sanctuary (proposed by Brazil and Argentina) further aids protection.

Regulations to reduce vessel speeds and modify fishing gear (like breakaway lines) have significantly reduced whale fatalities.

Whale-watching tourism has replaced whaling as an economic driver in many countries (e.g., Australia, Hawaii, and Iceland). Increased awareness of the negative effects of whaling has led to the implementation of global conservation policies.

Population Recovery:

- In the North Pacific, humpback whale numbers have rebounded from fewer than 1,500 in the 1960s to over 21,000 today.

- In the South Atlantic, populations have recovered from just 450 in the 1950s to over 25,000 now.

- Some populations have seen an annual growth rate of 10–12%.

- In 2016, the IUCN removed many humpback whale populations from the Endangered Species List, though some (like those in the Arabian Sea) remain critically endangered.

Green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) were once heavily exploited for their meat, eggs, and shells, leading to dramatic population declines worldwide. Their slow reproductive rate made them especially vulnerable to overharvesting.

Legal protections, such as Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), have banned international trade, while the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) has provided strict protections since the 1970s. Many countries have also prohibited the hunting and trade of green turtles.

Nesting beach protections, including Turtle Exclusion Devices (TEDs) in shrimp nets, have reduced bycatch, and protected areas in Florida, Costa Rica, Mexico, Australia, and the Galápagos Islands have safeguarded critical nesting sites.

Conservation measures such as night patrols, beach clean-ups, and restrictions on artificial lighting have further increased hatchling survival rates. Community-led conservation efforts have also been instrumental, with ecotourism replacing turtle hunting in places like Tortuguero, Costa Rica, and Indigenous-led programs protecting nesting sites in Hawaii. Additionally, hatchling protection and head starting programs relocate eggs to safer areas and rear hatchlings in captivity before releasing them into the wild.

As a result of these efforts, green turtle populations have rebounded significantly. In Florida, nesting numbers have surged from fewer than 50 in the 1980s to over 10,000 per year on some beaches. Costa Rica’s Tortuguero population has increased by over 500% since conservation measures were enacted, while Hawaii has seen a 5% annual increase in nesting females over the past three decades. The Northern Great Barrier Reef population remains stable, though climate change remains a concern.

Despite these successes, challenges persist. Rising temperatures are altering nest incubation, resulting in skewed sex ratios favoring females. Plastic pollution continues to threaten both juveniles and adults as well as poaching and illegal trade remain problems in some regions. However, the remarkable recovery of green sea turtles highlights the effectiveness of legal protections, habitat conservation, and local engagement in restoring endangered species.

Gray wolves (Canis lupus) population declines resulted from habitat loss and human persecution. Protections under the ESA helped gray wolf populations recover in the Northern Rockies and Great Lakes regions. Reintroduction programs, like those in Yellowstone National Park, led to sustainable populations and ecosystem benefits, such as controlling overpopulated prey species. There are estimated to be 12,000 -16,200 gray wolves in North America, with about 5,000 in the lower 48 states

Bald Eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) experienced a population decline due to hunting, habitat loss, and pesticides. The U.S. banned DDT in 1972, and combined with ESA protections, bald eagle populations soared from just a few hundred breeding pairs in the 1960s to over 300,000 individuals today. The protection measures emplaced led to the removal of Bald Eagles from the Endangered Species List in 2007.

The Future of Rice’s Whales

These examples highlight how strong legal protections, habitat conservation, and international cooperation can help restore animal populations that were once on the brink of extinction. The question remains: will efforts to protect Rice’s whales prevail, or will economic pressures take precedence? The answer will shape the future of marine conservation in the Gulf of Mexico for years to come.

Final Thoughts

The fight to protect Rice’s whales is not just about saving one species, it’s about setting a precedent for how we value and safeguard our oceans. While history has shown that conservation efforts can bring species back from the brink, it also reveals a hard truth: recovery is only possible when long-term protections outweigh short-term economic interests. The removal of ship speed limits in the Gulf of Mexico is more than a policy change; it’s a test of our commitment to preserving biodiversity in an era where industry often takes priority over the environment. If Rice’s whales disappear, it will be due to our failure to act. The true measure of progress is not just in what we build or extract, it’s in what we choose to protect. Will we learn from past successes, or will we allow one of the rarest whales on Earth to slip away?

Sources

NOAA Fisheries – https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/rices-whale

Leave a comment